This article originally appeared in World War II magazine. Reprinted with permission

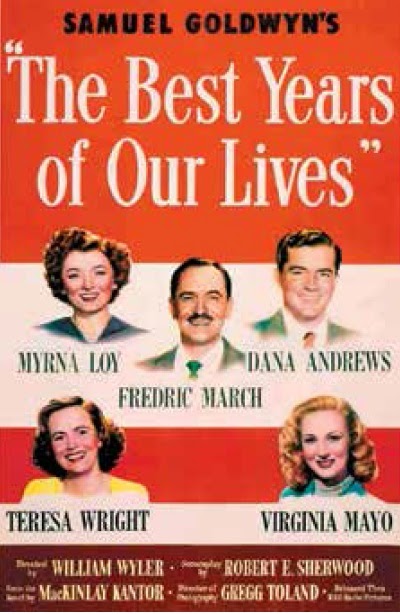

The Best Years of Our

Lives (1946) opens with the fortuitous meeting of three veterans returning to

Boone City, their home town. They are making the journey in the nose of a B-17 bomber. The oldest, Sergeant First Class Al

Stephenson (Fredric March) had been a well-to-do bank loan officer and family

man. Next is Captain Fred Derry (Dana

Andrews), an Army Air Corps navigator who had been a mere soda jerk before

enlisting. The youngest is Petty Officer

Second Class Homer Parrish, a star high school quarterback who had lost both

hands when the aircraft carrier on which he served had sunk. (The actor who played Homer, Harold Russell,

was an actual double amputee discovered by director William Wyler in an Army

training film. Russell had lost both

hands in a training accident.)

Homer wears

a pair of hook-like prosthetics, but impresses Al and Fred by his lack of

self-pity. He had served in the repair shop below decks, Homer explains, and

although he was in plenty of battles, he literally never saw combat. “When we were

sunk,” he says, “all I know is there was a lot of fire and explosions. I was ordered topside and overboard, and I

was burned. When I came to I was on a cruiser, and my hands were off. After

that I had it easy.”

“Easy?”

says Al incredulously.

“That’s

what I said,” Homer replies. “They took

care of me fine. They trained me to use these things. I can dial telephones, I

can drive a car. I can even put nickels in a jukebox. I’m all right. But...”

His voice suddenly trails off.

“But what, sailor?”

“Well,” Homer says; “Well, you

see, I’ve got a girl.”

“She knows what happened to

you?”

“Sure. They all know. But they don’t know what these things look

like.”

It is the

first inkling of the struggle Homer endures throughout the rest of the

film. He fears he will be pitied. He fears his girlfriend, Wilma, will find his

condition too much to bear. When the taxi that carries the three men to their

respective homes arrives in front of Homer’s house, Al and Fred witness his homecoming. Wilma embraces him, but Homer’s arms remain

stiffly at his side.

The cab

pulls away. Fred comments, “You gotta hand it to the navy. They sure

trained that kid how to use those hooks.”

trained that kid how to use those hooks.”

“They

couldn’t train him to put his arms around his girl, to stroke her hair,” Al

quietly observes.

As the film

unfolds, Fred and Al face their own homecoming challenges. Fred discovers that his military experience

counts for nothing in the civilian world; he returns to the menial job he had

before the war. Al, having learned in

combat to judge men on the basis of character, not collateral, has trouble

adjusting to his former life as a banker.

He drinks too much and feels awkward with his family. But those

challenges pale in comparison to Homer’s.

When the three men rendezvous at a bar owned by Homer’s uncle, Homer

betrays frustration. “They keep staring at these hooks,” he says of his family,

“or else they keep staring away from ‘em. Why don’t they understand that all I

want is to be treated like everybody else?”

Unable to

bear the pity, Homer retreats from his family and from Wilma. Finally, late in the film, Fred persuades him

that he has a good thing in Wilma and should not let her go. Homer agrees.

He then finds Wilma, takes her up to his bedroom, and shows her what it

would be like to spend the rest of her life with him.

Quietly,

matter of factly, Homer demonstrates that he can remove the harness that holds

his prosthetics in place. He then wiggles

into his pajama top, but cannot button it. Wilma does it for him. “This is when I know I’m helpless,” Homer

tells her. “My hands are down there on

the bed. I can’t put them on again without

calling to somebody for help. . . . If

that door should blow shut, I can’t open it and get out of this room.” He tells Wilma that having witnessed this, “I guess you don’t know what to say. It’s all

right. Go on home.”

“I know

what to say, Homer,” Wilma replies. “I

love you. And I’m never going to leave you. Never.” It is not only Wilma who feels that way. Homer’s family and friends have loved him all

along. But until this moment he could

not accept it. The film concludes with

Fred and Al attending Homer’s wedding.

Fred has found a decent job (helping to scrap the very bombers in which

he once flew). Al has made peace with his own job and reconnected with his

family. And Homer has found nothing

short of redemption from the loveless existence he feared awaited him.

The Best Years of Our Lives proved

a stunning success. It won nine Academy

awards, including Best Picture, Best Director (William Wyler, who was himself a

returning veteran), and Best Actor (Fredric March). Harold Russell was nominated for Best

Supporting Actor but considered such a

long shot that the Academy created a special award for him “for bringing hope

and courage to his fellow veterans through his appearance.” Yet in fact he did

win Best Supporting Actor, the only actor ever to receive two Academy Awards

for the same performance.

Although

much of the film’s success owed to its superb script and performances, it also offered

a strong rebuttal to a debate then raging about whether the millions of returning

veterans could re-integrate into society. A host of social scientists and psychiatrists were

predicting that many veterans would be unable to adjust to civilian life without

major psychiatric intervention. “The

thing that scares me most,” says Al early in the film, “is that everybody is

gonna try to rehabilitate me.” Few movie-goers could miss the significance of his

remark. But The Best Years of Our Lives dramatically argued that these fears

were misplaced. And no character in the

film illustrated it more eloquently than Homer Parrish.